14min read

After the successful demonstration of their cal.: L800 at the Chronometer competition of the Neuchâtel Observatory in 1964 and again in 1965 (winning in the category of electronic marine chronometers) and winning in the category of electronic pocket chronometers in 1966 with their L400 – quartz-hybrid system, Longines and B. Golay SA tackled the development of their own wrist watch sized quartz movement, despite Longines being involved in parallel in the development of the future Beta 21 movement with the CEH. As the quartz developments at the CEH seemed not to advance fast enough (the shareholders were not informed about the advances until mid 1967) and Longines had already invested quite a lot of money in that project, it was decided to try and develop a cheaper ‘in-house’ alternative (1, 9, 11).

Although the main principles of the future wrist watch sized quartz movement (cal.: L6512), for the Longines ‘Ultra-Quartz’ model, differ from its L400 – quartz-hybrid predecessor, it is clear that the experience from the circuitry development of these earlier movements and the confidence gained by winning the electronic pocket chronometer category at the chronometer competition of 1966, would be helpful for the development of the wrist watch sized version (1).

Early vs. Late Prototypes

After initial problems with the concept of the motor, Jean – Claude Berney, at that time head of development at B. Golay SA in Lausanne, had the idea to lean the mechanical concept of the new caliber on the principles of the ‘Accutron‘ system, as the principles of the motor assembly for the L400 Pendulette were regarded as not transferable to a wrist watch sized caliber. Berney will be proven wrong by René LeCoultre, who later will adapt the principles of the cal.: L400 stepping motor for the Rolex ‘Oysterquartz’ (cals.: 5035 and 5055) (1, 12, 13).

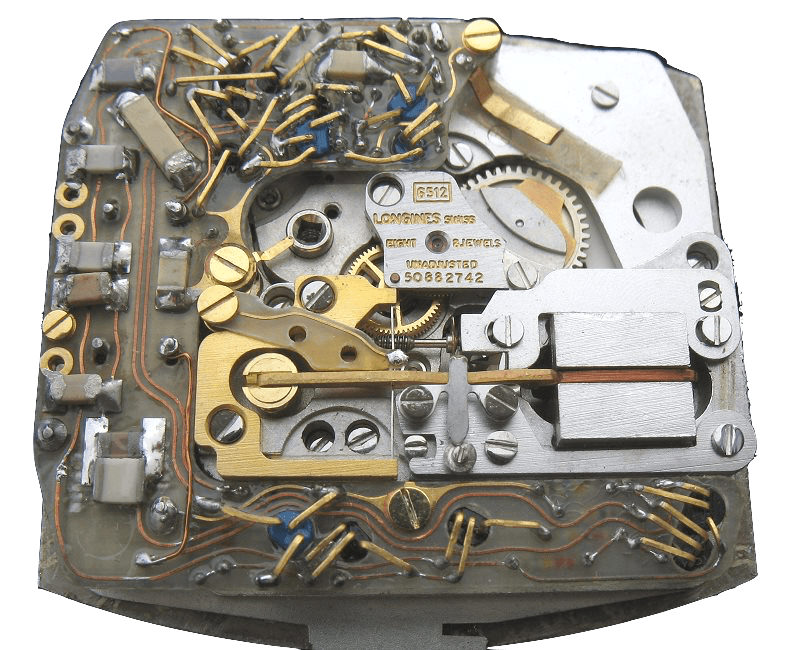

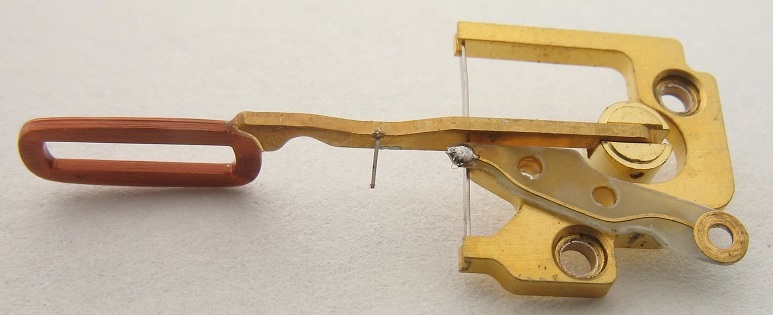

As for the ‘Accutron‘ and the ‘Beta 21‘, the motor would transfer its vibrations to an index finger, which activates an index wheel. A ‘stop index’ would avoid the index wheel to turn ‘backwards’. However, the construction of this caliber imposed, that the index wheel would sit perpendicularly to the motor axis and transmit the power to a worm gear interacting with the wheel train (1, 12).

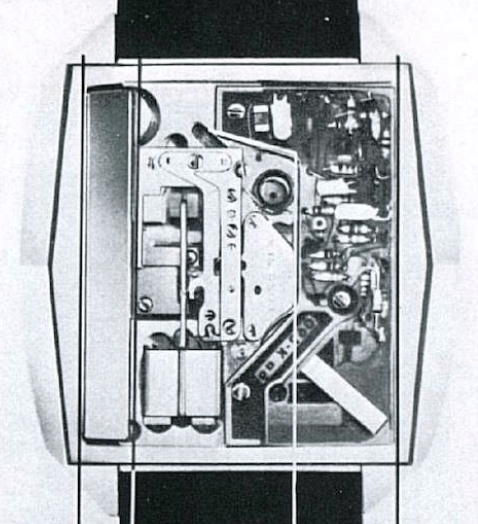

Berney hypothesised further, that the oscillations of the tuning fork assembly would be autonomously synchronised with the high frequency oscillations of a quartz, reduced by means of an electronic circuitry. The initial developments starting in late 1966 produced a prototype version with a 8192Hz quartz. This movement had the two oscillators linked through a series of discrete electronic components. The declared number and distribution of discrete elements (40 electronic elements are used in all: 14 transistors, 19 resistors, 7 capacitors) is taken from the 1969 press release and the Basle Fair 1970 documentation, showing this ‘early’ prototype version. Most probably these numbers slightly vary for the ‘later’ prototype version and the marketed version (1, 5, 14).

This ‘early’ prototype, which was working by 1969, was discarded in March 1970 for an updated version with a 9350Hz quartz, see explanations below. The overall design and the model name ‘Ultra-Quartz’ for the future model were already finalised in 1969, and would be transferred through the ‘late’ prototype versions to the production model. The caliber principles of the two prototype versions are the same, but the technical details of the ‘early’ prototypes are slightly different, hence one has to clearly separate the descriptions concerning the ‘early’ as compared to the ‘later’ prototype version. For reliability purposes and the possibility to transfer the description to the marketed model, following working principles are thus described for the ‘later’ prototype version (1, 3).

The (maybe) First Cybernetic Watch Movement

This movements two oscillators are linked through a series of discrete electronic components. The wheel train is actuated by the exposed vibrating bar of the motor, which vibrates at declared 170.66Hz between two permanent magnets, made of very expensive platinum-cobalt. Each pulse of the motor is compared by the electronic circuit to the reduced pulses of the bar shaped quartz crystal, which oscillates at 9350Hz (1, 11).

The quartz frequency of 9350Hz is reduced by a chain of discrete electronic components to 170Hz. The main feature of the electronics is to synchronise the reduced reference 170Hz from the quartz with the 170.66Hz from the motor. The frequency of the motor is regulated never to be exactly 170Hz, thus an ‘error’ of 0.66Hz is inbuilt, so the phase of the motor oscillations is constantly and automatically synchronised by the electronic circuitry to match the reduced quartz oscillations. If the motor is too slow, up to 5 impulses are given by the circuitry to accelerate the motor frequency to 170Hz. If the motor is too fast, impulses are given to the motor to slow down to exactly 170Hz (1).

This feedback -and correction loop was called ‘cybernetic‘ by Golay (in this context, self-regulating by feedback loop). The concept of a ‘cybernetic’ movement will be integral part of the later marketing for the watch. The same principle of ‘cybernetic’ feed back loop had been independently and simultaneously used during the development of cal.: 1500 by the Battelle Institute in Geneva for Omega’s high frequency quartz caliber, see dedicated section (1, 4).

The big advantage of this complex electronic phase synchronisation system is, that there is no need of energy draining electronic frequency dividers in form of integrated circuits as used for the CEH Beta series (Beta 1, Beta 2 and Beta 21) or by Battelle for Omega’s high frequency caliber. The discrete frequency dividers in cal.: L6512 need very low energy. So, one problem the ‘Ultra-Quartz’ did not share with the CEH Beta quartz project or Omegas early high frequency prototypes was energy supply (1, 9).

The use of discrete elements to construct the electronics, had also been the case for the L800 and the L400-quartz prototypes, and was forced by the fact that, to the contrary of the CEH and Battelle, Golay SA did not have clearance and licences from the US authorities to use their semiconductor technology. These would have been necessary, if wanting to develop their own integrated circuits. The purchase of prefabricated American elements (anyway not directly compatible for wrist watch calibers) would have been too expensive on short term and was no option (1, 9).

The electronic circuitry of both prototype variants including the marketed version was developed and built at the B. Golay facility in Lausanne, whereas the mechanical components of the wheel train and the motor would be refined and build by the ‘Record Watch Company’, which belonged already to Longines since 1961. The quartz elements would be bought from Ebauches SA (Oscilloquartz). This developmental project, comprising the collaboration of Longines, Record Watch Co. and Golay SA would be code named ‘Hourglass’ (1, 11).

The initial miniaturisation from the L400 pendulette and prototyping took 3 years until the Swiss patent for the complete calibre of the ‘early’ prototype version was granted in August 1969. As for the Beta 21 movement, the path to industrialisation would be paved with problems, such as massively delaying the commercial release of the ‘Ultra-Quartz’ model (5, 9, 11).

Industrialisation – Longines ‘cal.: L6512’ vs. CEH ‘Beta 21‘

Even after several years of development and two prototype versions, the definitive cal.: L6512 was extremely complex to construct, but draws less power than the early bipolar integrated circuits used by the CEH Beta team. As for Beta 21, one of the most problematic technical issues was the suspension of the quartz bar within its metal case, the movement thus being extremely sensitive to shocks. To the contrary of Beta 21, these quartz suspension problems went unnoticed during functional testing and could not be solved for cal.: L6512 before the launch and thus many ‘Ultra-Quartz’ watches stopped to work. The reason for not noticing the peculiar quartz suspension flaws, was the lacking testing with appropriate dynamic testing rigs and the missed opportunity to test the prototypes at the Observatory in Neuchâtel, as was done for the Beta 21 prototypes (1, 4).

Therefore, the industrialisation of cal.: L6512 faced identical problems as the industrialisation of the Beta 21 movement resulting in huge delays for production:

Technology transfer: Logistic problems linking the external prototyping departments (Golay (electronic components) and Record (mechanical components)) to Longines’ production facility, see below. Also the development of Beta 21 suffered from a slow technological transfer from Beta 2 (3).

Quartz problems: Problems with the reliability of the suspension of the quartz crystal (the quartz crystal assembly having been sourced from Oscilloquartz (part of ESA), the same source as CEH used for their quartz assembly for the Beta 21 movement!) (1)

Golay managed to produce the 10000 electronic modules ordered by Longines, all assembled by three ladies at the B. Golay SA facility in Lausanne, who could manipulate and solder the tiny circuitry elements with highest precision. After assembly, each electronic module was tested (not shock tested) and regulated. Due to the mentioned timing problems, only a fraction of these electronic modules would be used for watch production. The rest was kept and used for servicing purposes, but was ultimately destroyed when Golay went out of business in 1975 (1).

Industrialisation – Longines ‘Ultra-Quartz’ vs. Seiko ‘Astron’

Longines’ ‘Ultra-Quartz’ had been announced in the press as the first commercial quartz wrist watch the 20.08.1969, just eight days after being granted the Swiss patent for the complete movement assembly and earlier as other Swiss companies or their international concurrents such as Seiko. However, this marketing stunt could not divert from the internal strategy differences of Longines (and all other Swiss brands) as compared to the well organised Seiko, which ultimately won the race for the first commercialised quartz wrist watch (3, 9, 11; Seiko ‘Astron’ picture credits: 8).

Seiko’s prototyping department for electronic watches, lead by Tsuneya Nakamura, was completely integrated into the production system since the beginning and the prototypes were designed in clear view of future mass production. Thus, the same engineers who developed quartz wrist watch prototypes, also worked in parallel on the implementation and adaptation for automated assembly lines (3, 11, 15).

Whereas, at Longines, the prototyping department for electronic watches took place in a small, isolated unit located physically and logistically outside the company’s production system. Moreover, since the beginning of the Longines – Golay collaboration, the quartz time pieces were developed to participate to chronometer competitions, neglecting the planning for a future technology transfer for mass production (3, 11).

Many practical difficulties thus appeared when in March 1970 Longines’ engineer Claude Ray had been trusted to oversee the industrial production of the mechanical modules for the ‘Ultra-Quartz’, to engage into the technology transfer and enter the production phase of the ‘Ultra-Quartz’. To the contrary of Seiko, Longines (and Golay SA) had failed to develop prototypes from the perspective of serial production and to organise workshops to support the mass-production. The same strategy was used by the CEH for the industrialisation of the Beta 21 movement, also contributing to the delay for its industrial production and release (3).

Finally, starting March 1970, cal.: L6512 had to be redesigned, the quartz frequency had to be recalculated (8192Hz was abandoned for 9350Hz), and thus a new circuitry had to be developed, creating the aforementioned ‘late’ prototype version. In February 1971, Ray’s team delivered the first 50 watches to the sales department. These updated versions were to be introduced at the Basel Fair 1971. Despite these difficulties, another attempt at mass production was made with 200 pieces in August 1971. Unfortunately, several problems delayed the distribution further. Although the official launch was in October 1971, it was only in early 1972 that most ‘Ultra-Quartz’ models were delivered. Ironically, the Longines quartz model ‘Quartz-Chron’, with Beta 21 caliber, was distributed before the ‘Ultra-Quartz’. For the mentioned reasons, it would take over two years for the production version of the ‘Ultra-Quartz’ model to be released for sale. In the end, around 2000 Longines ‘Ultra-Quartz’ models, in two different case versions, would be produced between 1971 and late 1973 (3, 4, 10, 11, 12).

As implied above, on a broader time scale, it was already starting from 1964 that the management of Longines had neither the capital nor the interest to make massive investments to transform product development and production technology to suit the production of electronic watches (machines, tools, automation and workshops), revealing the underestimation of the future importance of the quartz system for commercial wrist watches. These crucial judgement errors contributed massively to the delay in production of the ‘Ultra-Quartz’ as compared to Seikos ‘Astron’, which was successfully commercialised starting December 1969, emphasising Seiko’s commitment to the quartz system (3).

As mentioned above, for Seiko there was no need for an elaborate technology transfer from prototypes to industrial versions, as all aspects of production were integrated into the prototyping, speeding up and streamlining the processes early in the conceptual phase and thus saving precious time (3, 5, 9).

After Sales Problems

Cal.: L6512 is a very complex movement, which despite entering industrial production, still required extensive manual intervention for assembly and regulation. The coil of the motor needed to be glued by hand to its support, the 40+ discrete elements constituting the electronics had to be hand soldered one by one to their support. However, these procedures did not decrease the movement’s reliability. The main reason leading to many ‘Ultra-Quartz’ models to irreversibly fail, was the flawed quartz suspension not suited for severe shocks, such as dropping the watch. One other issue represented the index finger (and stop index) on the motor, which often did not survive severe shocks either. These problems were solved by the after market service by replacing motor elements or the complete electronic element containing the quartz assembly, respectively (1).

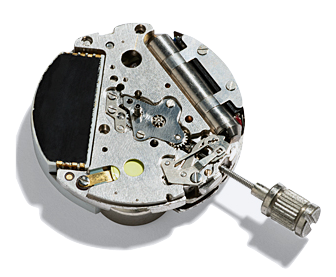

Unfortunately in 1975, after the bankruptcy of B. Golay SA, who ensured the after sales service for the ‘Ultra-Quartz’, all electronic spare elements, and allegedly also the ‘early’ prototypes and documentation were disposed of, so the after sales service for the ‘Ultra-Quartz’ could not be guaranteed using original caliber elements any longer. One alternative then implemented by Longines was to replace cal.: L6512 with cal.: L7442 (ESA quartz caliber) or L729.2 (ETA 940.111). Consequently the ‘Ultra-Quartz’ cases had to be adapted to accept a crown at ‘3’. A movement holder had to be manufactured for a accepting the new, round movement. A modified case back would hide the former crown recess and hole and be adapted for the new position of the battery hatch. As the conversion to fit an ESA or ETA quartz movement needed extensive modifications, it is not known, if the customers had to participate to the costs or not (1).

The legacy of the ‘Ultra-Quartz’

The developments for a quartz wrist watch movement continued in the prototyping department at Golay in parallel to the development and modifications of Longines cal.: L6512 for the ‘Ultra-Quartz’ model. By late 1971 it was not necessary any more to circumvent power consuming electronics, as low power CMOS integrated circuits (IC) suiting watch calibers started to be readily available and relatively cheap (1).

Ref.:

- Personal communication with a senior engineer directly involved in the prototype and watch developments and construction at B. Golay SA from 1965 to 1975.

- Linder P.; Au Coeur d’une Vocation Industrielle: Les mouvements de montre de la maison Longines (1832-2009) Tradition, savoir-faire, innovation, Edition de Longines 2010, courtesy of Longines’ Heritage Service

- Donzé P.Y., Dynamics of Innovation in the Electronic Watch Industry: A Comparative Business History of Longines (Switzerland) and Seiko (Japan), 1960-1980, The Journal of the Economic & Business History Society , © 2019, The Economic and Business History Society.

- Grail Watch Reference

- Europastar

- Electric Watches

- Crazywatches

- Seiko Design

- Personal communication with a former Executive Vice-President of Ebauches SA, in charge of Research & Engineering

- Watchonista

- Trueb L. F., Ramm G., Wenzig P.; Die Elektrifizierung der Armbanduhr; Ebner Verlag, 2011

- Bramaz H.-R., Baumann H.; Die Elektrische Armbanduhr, Band 1, Verlag Stutz Druck AG, Wädenswil, 2013

- Goldor

- Longines press release, 20.8.1969

- Fratello Watches

- Plus9Time