9min read

Being the first watch system completely disposing of the need for a balance, the tuning fork system was regarded by the Swiss watch making industry as the main base for future developments. All watchmaking companies wanting to enter the development of revolutionary battery driven systems would be confronted with the need to avoid the 1953 ‘Accutron‘ patent, discouraging some manufacturers to pursue the developments and motivating others to research systems then thought to be pure science fiction. The Swiss new, that one way to regain the technological supremacy would be to bring the person responsible for the Accutron development back to Switzerland at all costs (7).

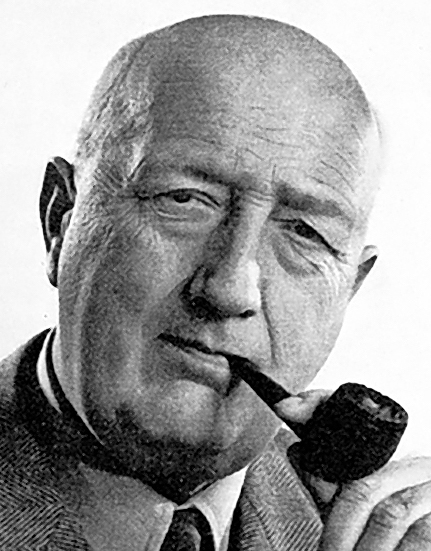

On behalf of the CEH, Sydney de Coulon, then director of Ebauches SA travelled personally to New York and recruited Max Hetzel, inventor of the ‘Accutron‘ tuning fork system, to return to Switzerland in late 1963. De Coulon made Hetzel an offer he could not refuse, allegedly tripling the salary Hetzel gained at Bulova. To take full advantage of Hetzel’s experience in developing and industrialising a new watch system, he was given the lead of the LSRH (Laboratoire Suisse de Recherche Horlogère), which was working in parallel with the CEH, where he should develop an ‘all Swiss’ tuning fork movement by avoiding all conflicts with the said Bulova patent of 1953 (6, 7).

Although administratively the LSRH would be considered part of the CEH, the two institutions CEH and LSRH would be factually independent and not even exchange expertise at the beginning, although starting from 1964, progress reports of the LSRH would be integrated into the CEH reports described as coming from the ‘Ligne Pilote’. In these reports Max Hetzel was referred to as director of the ‘Ligne Pilote’. The fact that Hetzel was referred to as ‘director’ was part of the deal with Sydney de Coulon, as Hetzel did not want to be a subordinate of another leading person when returning to Switzerland (7).

The project Hetzel would be leading was one of three tuning fork based research topics during the first three years of the CEH (1962 -1965). Hetzel managed to advance his project of developing an all Swiss tuning fork movement faster than the other two tuning fork related CEH-projects, Alpha and Beta (6, 7).

Hetzel was not among the believers of the quartz revolution and when in late 1965 it became clear, that the CEH would redirect the efforts from researching the tuning fork system to the quartz regulation, Hetzel categorically refused to work on the development of a quartz watch, which he deemed impossible. The reason not being the principle of using quartz as a resonator, which he was aware to be superior to the tuning fork, but he saw no industrially compatible way to solve the problem to provide the high amount of energy needed to run such a wrist watch (3).

The first caliber which was developed by Hetzel’s group was given the number ‘151’ and the project was named ‘Swissonic’ by Hetzel himself (1).

The Breakthrough: Caliber 151

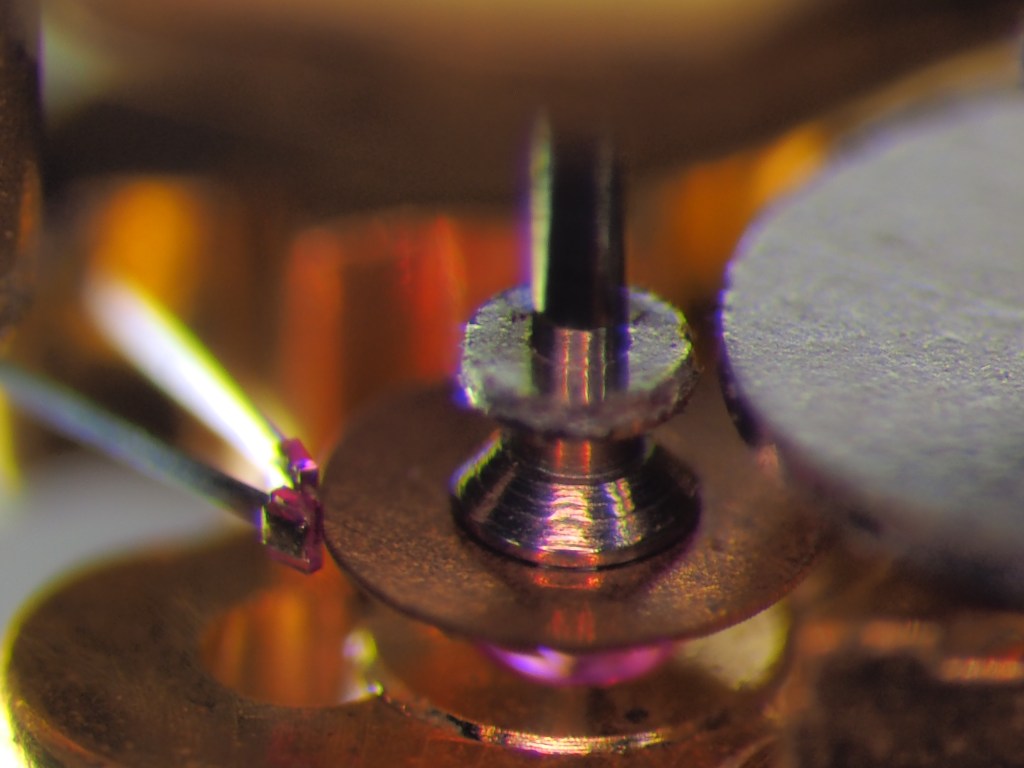

Even with the paradox of needing to avoid the use of technology of his own revolutionary invention, Hetzel together with a team of 5 engineers managed to develop and construct a movement with a ‘W’ shaped tuning fork vibrating at 480Hz and the construction potentially avoiding position errors due to the higher frequency and the highly symmetrical tuning fork. Latter position errors being the biggest functional disadvantage of Bulova’s original system (2, 3, 5).

This very first version of the new caliber had eccentric hands, a date window at ‘6’ and was numbered 151. This caliber was developed starting from the employment of Max Hetzel in 1963 and ended in July 1966. In parallel to the execution of cal.: 151 a new caliber (153) with the same construction principles of cal.: 151 was developed, but with central hands this time. Two reasons motivated the change: it was easier and cheaper to fix the indexing fingers onto the resonator for central hand activation and marketing research revealed, that customers preferred centrally located hands to an eccentric construction. Moreover, the servicing of this ‘centralised’ version would be easier (1).

In parallel to the development of cal.: 153 and the testing of the earlier cal.: 151 (cal.: 151 was later completely dropped in favour of cal.:153) the planning of the production line for the ‘zero – series’ of cal.: 153 was started in July 1966, with a planned production of 50 prototypes between October 1966 and April 1967. The long term plan was to have a production line for a ‘zero – Series’ of 5000 calibers by late 1968. The production line would only need 65 operations to build the calibers and would employ 30 people (1).

The planning for development and the industrial production of this ‘Swissonic’ caliber reflects the experience Hetzel had with the industrialisation of the ‘Accutron’ a few years before. To the contrary of the development of ‘Beta 21‘ and also Longines ‘Ultra – Quartz‘, where development and industrialisation were completely separated, Hetzel, probably without knowing, adopted the ‘Seiko protocol’ of integrating production aspects into the development and thus speeding up industrialisation of the caliber. Seiko adopted this way of development from the American method used already during the late 19th century.

Caliber 153

One important feature of the new calibers 151 and 153 is the W-shaped resonator. Hetzel already had the idea of this shape of resonator while still working for Bulova. He theorised, that in order to get rid of the position errors encountered with the ‘Accutron’ system, one would need longer resonators, resonators of higher frequency or both. Both aspects being realised in this caliber. Hetzel had no time to integrate his new idea at Bulova, Sydney de Coulon had recruited him to return to Switzerland, before the implementation of the new system (3).

The other revolutionary thought integrated into this caliber, is the use of magnetic pinions and wheels thus an ‘elastic’ coupling of the indexing wheel with the wheel work, eliminating inertia and also allowing a higher frequency. This principle will be further developed and refined to create the ‘oil box’ for cal.: 1220 (date) and cal.: 1230 (day/date) used in the ‘Megasonic’ model Hetzel will develop for Omega starting 1969 (1, 3).

Observatory Testing

This cal.: 153 ‘Swissonic’ underwent different tests, also at the Observatory in Neuchâtel between December 1966 and November 1967. Earlier prototypes of the ‘Swissonic’ caliber were submitted for competition at the Observatory in Neuchâtel in 1965 already and their performance disappointed, especially because of remaining position errors, not relevant for daily use, but crucial imprecisions during chronometer competitions. The reaction to get rid of the position errors and to increase precision was to create a ‘Swissonic’ version at 720Hz, which in the chronometer competition of 1966 will reach N = 2.25. Despite the excellent result ranking 4th in its category of ‘electronic wrist watch chronometers’, it will be beaten by ESA’s new development, the MOSABA caliber, which will take the first three ranks. Also, the new frequency of 720Hz will be integrated into the later development of Omega’s ‘Megasonic’ movement (1, 4).

Unexpected Bad News

It was envisioned to contact the industry before the end of April 1969 and to produce 200’000 movements per year, but by the time movements for a ‘zero-series’ started to be produced, the news broke by the company lawyers, that the new ‘Swissonic’ movement still infringed the Bulova patent and could thus not be marketed without Bulova’s consent and license. Consequently the further development of the ‘Swissonic’ movement was abruptly abandoned at the end of 1968, all research on it was dropped and most of the built prototypes were destroyed (1).

CEH sold the project including ‘its engineers and Max Hetzel’ to Omega, the contract being effective starting from 1.4.1969. Hetzel continued the development for Omega until creating their own tuning fork movement they later named and marketed as ‘Megasonic’. A few CEH-Swissonic prototypes have been transferred from the CEH to Omega and again modified to run with 720Hz. These modified and ‘updated’ prototypes will be entered for competing at the Observatory in Neuchâtel in the category of ‘acoustic pocket chronometers’ in 1969 through 1971 circumventing the abolition of the chronometer competitions for wristwatches starting 1968 (2).

As Hetzel came up with the name ‘Swissonic’ while working at CEH, according to Swiss law, the copyright for the use of that name belonged to CEH. Upon withdrawal from research into that movement, the name was sold to ESA where it was used to promote their own lines of electric and electronic movements: ‘ESA-Swissonic’ 10, 100, 1000, 2000; cal.: 9150, 9162, 9180, 9260 respectively (2). Therefore, one needs to separate two different watch categories named ‘Swissonic’: The original Hetzel-CEH-prototypes and the later and different ESA versions for witch the name ‘Swissonic’ was reused (7).

The original CEH-Swissonic prototypes by Max Hetzel’s have no developmental relation to ESA’s ‘Swissonic’ models, and to the contrary of some sources, Hetzel never worked for ESA or on the MOSABA caliber (2, 7).

Ref.:

- CEH Seminar report of the 7.2.1967

- Bramaz H.-R., Baumann H.; Die Elektrische Armbanduhr, Band 1, Verlag Stutz Druck AG, Wädenswil, 2013

- Hetzel M., Technische Rundschau, Nr. 19, 26.4.1963

- Observatoire Cantonal de Neuchâtel, Rapport sur le concurs chronométrique 1966

- Perret T., Beyner A., Debély P., Tissot T., Jeanneret F.; Microtechniques et Mutations Horlogères, Editions Gilles Attinger, 2000

- Roger Wellinger Archive

- Personal communication with a former Executive Vice-President of Ebauches SA, in charge of Research & Engineering.

- Le Courier

- Grailium

- ETA

- Europastar