9min read

Gérard Bauer, lawyer and newly appointed president of the Fédération Horlogère (FH, leading trade association of the Swiss watch industry) was confronted with the unofficial announcement concerning the launch of Bulova’s ‘Accutron‘ in late 1960, already in July 1960 during the visit of General Omar N. Bradley (chairman of the Board at Bulova) in Bienne, where the two met. For Bauer, the imminent launch of this revolutionary new wrist watch system fuelled fear to lose leading positions on the international market (3). Quite quickly under the leadership of the FH, the impulse was given to create a new Swiss competence center for microelectronics, next to the already existing LSRH (Laboratoire Suisse de Recherche Horlogère). The goal would be to create an electric Swiss wrist watch, which would show at least double the precision of the ‘Accutron’. This was realised by assembling a big group of Swiss watch -and parts manufacturers under the leadership of the Federation Horlogère (FH) and Ebauches SA (ESA) to join in a common stock company later called ‘Centre Electronique Horloger’ (CEH). (1, 3, 4)

The first engineer to be recruited for the new competence center was Roger Wellinger, in September 1960, who after receiving his PhD at the ETH in Zurich in 1946, spent almost 10 years in the USA among other projects researching transistor technology for General Electric. Wellinger, having been in de USA for over 10 years had access to a network of fellow Swiss engineers working in the field of microelectronics in the USA and was thus charged by the Swiss with recruiting highly specialised Swiss microelectronics engineers willing to follow him back to Switzerland for working at the CEH in Neuchâtel (3, 4).

The CEH will be officially inaugurated the 30.01.1962. Wellinger, appointed director of the CEH from the start, managed to convince 10 highly specialised Swiss engineers to set up a complete research and development laboratory from scratch. The facilities, which at the beginning were running with 75 employees, were conceived to house development and pilot production for electric calibers and integrated circuits (3, 4).

Centre Electronique Horloger (CEH), Neuchâtel

The goal set up by the Swiss watch industry by forming the CEH, was to develop electric wristwatches at least of double the precision of the ‘Accutron’. To be clear: the goal was to develop an electric watch in strict compliance with the directives of the governing board (Fritz Hummler, president) and the Swiss watch industry, not to engage in new principles such as quartz, but to create a Swiss tuning fork system, better than the ‘Accutron’ (1, 3).

From the very beginning, Omega was highly interested in engaging into the research for a quartz system at the CEH, as they were secretly working with Battelle on their high frequency quartz caliber since 1957 with little progress, but their enthusiasm for quartz was cut short, as they were by large not the most influential shareholder of the CEH. The main reason behind the directive concerning the improvement of the tuning fork system is, that Ebauches SA, shareholder at 39.5% of the CEH, already was working on a tuning fork system in all secrecy (the future MOSABA caliber) and they firmly believed that the tuning fork system would be the wrist watch system of the future (3).

Therefore, following the directives of the shareholders (mostly Ebauches SA), Roger Wellinger’s strategy for the emerging CEH consisted mainly of three elements (6):

A) Recruiting and hiring Swiss engineers, who have spent a certain time in America and are willing to come back with the idea of importing technical and scientific know-how from the US to Switzerland especially in the area of semiconductors and circuits.

B) Investigating of all kinds of possible subsystems and later on develop new kind of solutions similar to the morphology developed by Prof. Fritz Zwicky, Caltec. Especially in the area of sonorous resonator (see Accutron), frequency dividers and displays. There had been a great deal of various investigations taken place resulting in a fairly complete catalogue of possibilities.

C) Build up semiconductor expertise in Switzerland.

Amongst others, Wellinger persuaded Kurt Hübner, student of semiconductor pioneer William Shockley. Hübner was a physicist with experience in semiconductors and an indispensable asset, as Wellinger recognised the importance of an own semiconductor laboratory. That was the only way to become independent from foreign suppliers and this would at the same time allow to investigate into dedicated research and create a more sophisticated tuning fork system, by the integration of advanced electronics (1, 3, 4).

Other initial recruits were Rolf Lochinger, an electro engineer, with experience in semiconductor circuit design and magnetics and Armin Frei an electro engineer, with experience in semiconductor device design and circuits as well as atomic clocks. These three will play a leading role in later important developments (6).

Roger Wellinger’s approach for a successful developmental environment was to allow the engineers some freedom in researching the main topics required for the development of a new electric wrist watch system. It is the same approach, which was common in the US and which he had experienced for several years (5).

1962 – 1965: Alpha, Beta and Swissonic

The first studies concentrated on concepts with a minimum of components, based on charge accumulation and synchronisation of a secondary time base. They worked fine on demonstration models but turned to be incompatible with the emerging Integrated Circuits (IC) technology. The strategy and plan in the field for the development of electric, tuning fork regulated wristwatches until 1965 concentrated on three topics (1, 6):

1. Alpha Project (led by Heinz Waldburger), a wristwatch incorporating a figure 8-shaped metallic tuning fork resonator with reduced gravitational disturbances, otherwise similar to the ‘Accutron‘, but with the advantage to avoid position errors.

2. Beta Project (led by Max Forrer) incorporating a metallic tuning fork like the ‘Accutron‘, but newly with a small chain of frequency dividers to drive a separate vibrating motor.

3. Swissonic Project (led by Max Hetzel) where the newly recruited Max Hetzel (affiliated to the LSRH starting 1963) would try to circumvent his own patent for the ‘Accutron‘ system and produce a better and all Swiss tuning fork caliber.

The Alpha – Resonator Project

The Alpha project envisioned an electro-dynamic approach with a small circuitry controlling the resonator. To increase precision and the resistance to position errors the resonator was planned to be in the form of an ‘8’ and three dimensional instead of flat, it needed a special battery, and a delicate mechanism for the displaying the time. Unfortunately no prototypes are known to have survived, even if some early internal protocols of the CEH describe working, experimental laboratory prototypes. Moreover, two prototypes (Alpha-01 and Alpha-02) are known to have participated to the Neuchâtel Observatory competitions in 1966 in the category of ‘wrist watches with acoustic system’ (4, 6).

The Beta – Resonator Project

As explained above, this ‘early’ Beta project was concentrating on the use of a tuning fork regulator and the development of an electronic dividing chain using piezoelectric circuitry to drive a ‘magnetic’ vibrating motor. Despite the Beta resonator project being split into 8 different approaches, unfortunately none was advancing as expected, only producing negative results for several years. No working prototype is recorded from this research, despite the advances of the ‘integrated circuits lab’ in the development of the bipolar dividing chain and the progress of Henry Oguey in developing the vibrating motor (1, 3, 4).

This ‘early’ Beta project at that time was the only one incorporating two electromechanical transducers, the second transducer being an electromagnetic vibrating motor. Both, the research on the dividing chain and the vibrating motor will be kept for later developments involving a quartz regulator (1, 4).

A third resonator project was envisioned (Gamma – Resonator Project) using a miniaturised circuit, but not integrating the piezoelectric system into the circuitry as for the Beta – resonator project, but into the motor. latter project as well as a fourth idea using an electro-physico-chemical display was rejected early on to concentrate on the three projects (Alpha, Beta, Swissonic) mentioned above. The feature of not using the conventional hands to display the time, but an electro-physico-chemical display will lead to the development of the LED display system some 10 years later (4).

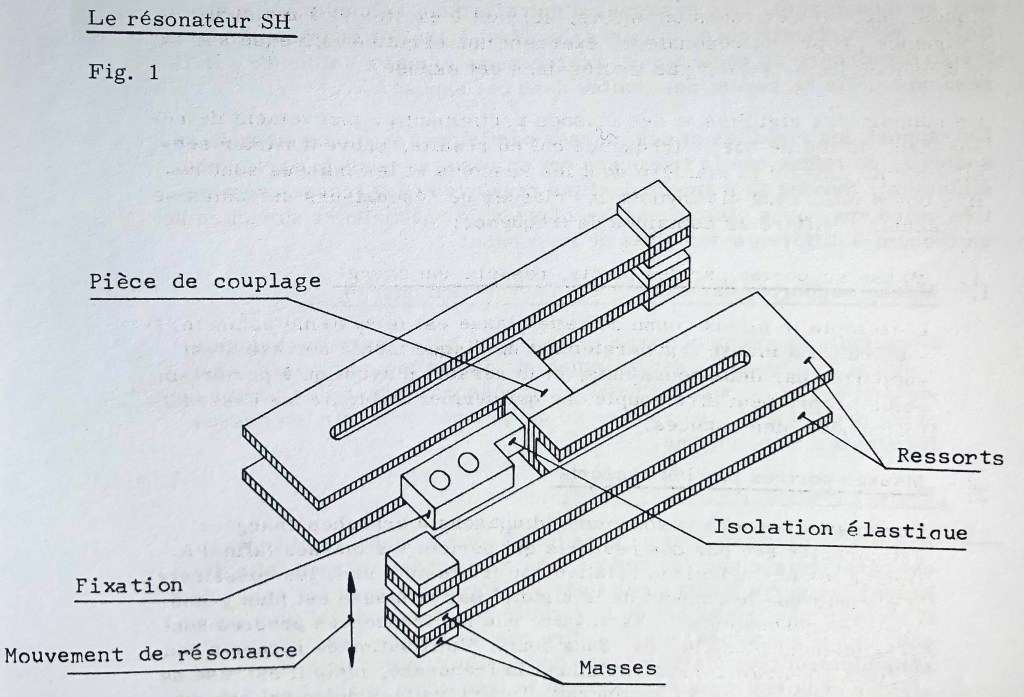

In 1964 engineer Armin Frei working for the Beta-resonator project got in charge of the resonator development, its transducers and the various driving circuits. The directives had been to develop so called sonor-resonators, resonating at around 400 to 800 Hz preferably with the shape of a tuning fork. The advantage of the tuning fork was its rigid suspension and its low frequency of oscillation at given length. Its disadvantage were its positional sensitivity to the earth gravitational field, its temperature sensitivity and its low factor of quality (Q). Various materials, principles of operations and driving schemes had been investigated, none of them was convincing when considering all parameters (6).

Two of the three main tuning fork resonator projects at the CEH were going nowhere. The absolute secrecy about the developments made the shareholders very nervous, and by 1965 they started to demand practical results, but little they new about the revolution which was about to be initiated.

Continues in subsection ‘Beta 1 – Beta 2‘

Ref.:

- Quartzwristwatch, Courtesy of Dr. Armin H. Frei Heritage Estate

- Piguet Ch.; Integrated Circuit Design Power and Timing Modeling, Optimization and Simulation 12th International Workshop, PATMOS 2002 Seville, Spain, September 11-13, 2002, B. Hochet, A. J. Acosta, M. J. Bellido (Eds.), Springer

- Personal communication with a former Executive Vice-President of Ebauches SA, in charge of Research & Engineering.

- Roger Wellinger Archive

- Personal communication with members of Roger Wellinger’s family

- Privately written notes by Armin Frei and Rolf Lochinger

- CEH archive at the MIH