19min read

1965: A New Strategy – The CEH goes Quartz

The very first quartz controlled device made at CEH was a quartz regulated demonstration model, scratch – built by engineer Eric Vittoz in 1962 in the size of a shoe box (31.5 x 30 x 27.5 cm, see pictures below). This shoe box sized demonstration model contained a 10kHz commercial quartz radio tube with oscillating circuit, analog frequency dividers and a commercially available electro – mechanical clock. Here, the quartz was used for convenience, to test a very primitive setup frequency division built by Kurt Hübner and to look at the power consumption and voltage of such semiconductor device. This setup was not built as a strategic element for watch development. Vittoz’ quartz clock was never shown to the members of the staff. Indeed, no trace of CEH working on quartz oscillator systems prior to 1965 is found in their archives (1, 3, 13, 15).

The 1.2.1965 Engineer Armin Frei, who had previous experience with quartz oscillators, presented a technical report about the combination of two low frequency (200Hz, tuning fork shaped!) quartz oscillators for the use in a wrist watch caliber, challenging seven other potential systems within the Beta resonator project, all working with a tuning fork resonator.

Later, the 7.5.1965, Frei informed colleague and engineer Rolf Lochinger about the continuous negative results encountered while working on the Beta – tuning fork resonator project and shared the idea to look further into the use of quartz crystal oscillators instead of putting all efforts towards the tuning fork system (1, 15).

His detailed, but still secret, proposal included the use of a single crystal quartz oscillator at acoustic frequency in the range of 10 kHz, miniaturise it by orders of magnitude down to dimensions required for wristwatches. The requirement of size and power consumption was here predominant. Rolf Lochinger proposed to investigate into electronic circuits suited to master increased divisional ratios. The new ‘quartz’ side-project, although approved by CEH director Roger Wellinger, was risky and definitely not to the mind of the cautious department head, Max Forrer, quite understandably sticking to the directives of the governing board, not to engage in new principles such as quartz, but would certainly have great impact on the watch industry if successful. With Wellinger’s blessing, Frei and Lochinger could start their initiative immediately and agreed mutually to investigate into this new idea (1).

As of September 1965 Rolf Lochinger and François Niklès started to develop electronic and mechanical models of quartz wrist watches. By the end of 1965, the team of Frei and Lochinger could present an impressive miniaturised quartz oscillator prototype of wrist watch compatible size. This remarkable result presented in November 1965, convinced Roger Wellinger, director of CEH and responsible for the yearly strategy and plan, to declare the “Montre-bracelet à quartz” to become the primary strategic goal for the year 1966. The other consequence was, that the inconclusive ‘early’ Beta – tuning fork resonator project trying to optimise the ‘Accutron‘ system by adding a piezo-electric circuitry and an electromagnetic motor was abandoned and replaced by a ‘new’ Beta – quartz project, where a quartz oscillator system would be researched (1).

These studies, completed in February 1966 with an integrated driving circuit for stepping motors, served as the basis for the Beta 1 part of patent applications initiated 14.2.1966. After extensive layout and packaging studies, Rolf Lochinger presented the first complete, integrated and packaged electronic system of Beta 1, in December 1966, on a small printed circuit board (16).

It must be emphasised, that Wellinger’s decision to engage into quartz research on a larger scale was extremely risky, as it represented the diametral opposite path which the governing board and thus the powerful Ebauches SA expected. This was also the reason why Max Forrer, head of the Beta – tuning fork resonator project was not sharing the same enthusiasm as Wellinger, Frei and Lochinger, as he understandably wanted to strictly follow the directives imposed by the governing board. Because of the hesitation of Max Forrer, Wellinger took on the lead of the Beta – quartz project himself (3).

1966: The ‘new’ Beta project

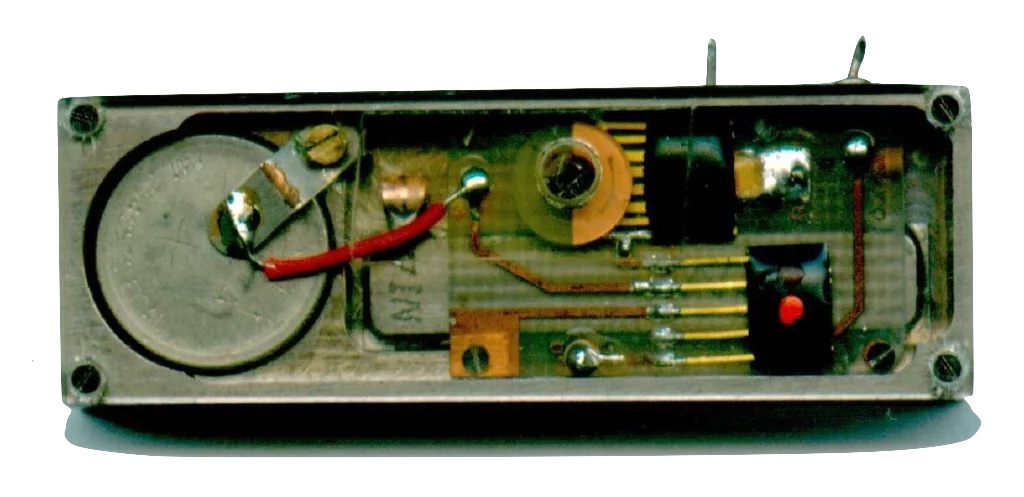

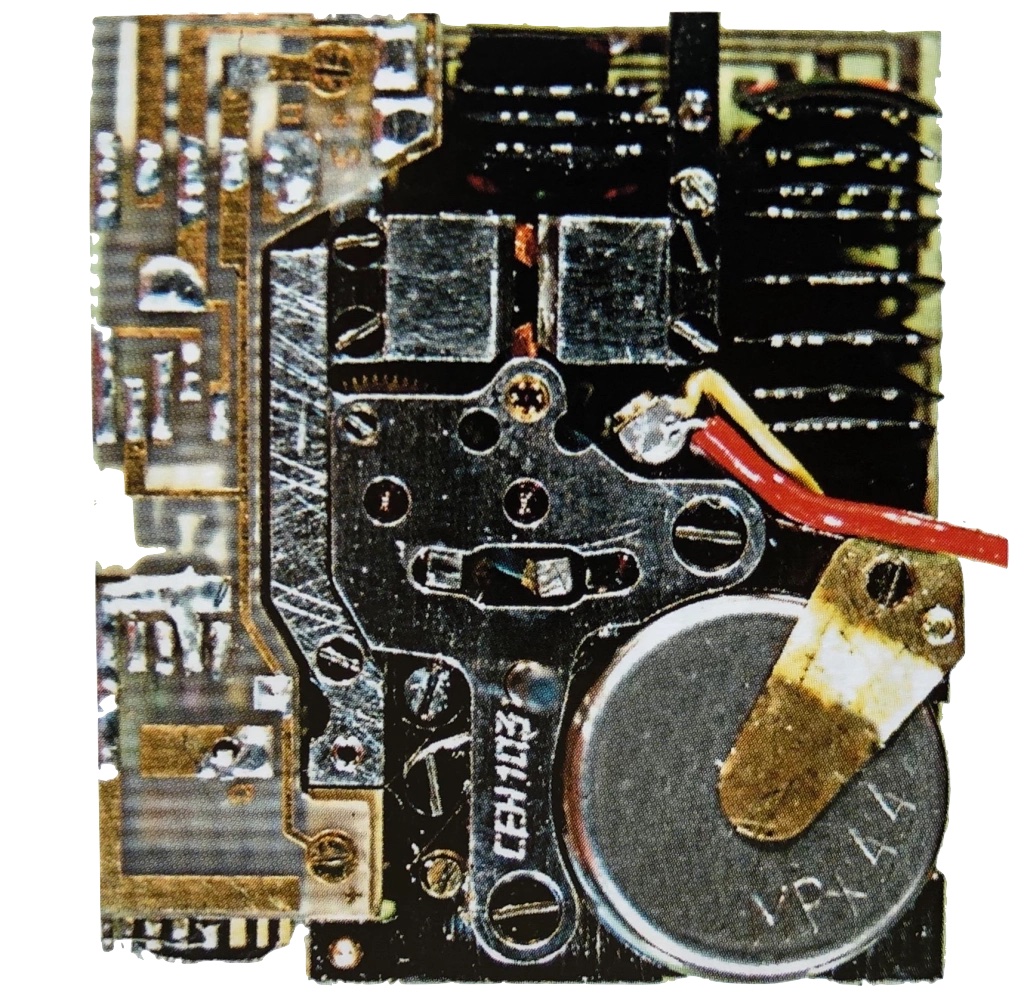

By the first quarter of 1966, Frei disposed already of a miniaturised quartz oscillator prototype with an 8192 Hz quartz resonator (see picture above), a novel fully integrated bi-polar quartz driver circuit running at less than 4 µA current consumption (black epoxy covered IC with red dot) and a primitive frequency division set-up (upper black epoxy covered IC without a dot), all these components survived until and including the industrial phase with minor improvements only (1).

The ‘new’ Beta – quartz project analysing the feasibility of a quartz wrist watch produced working laboratory prototypes, but especially the frequency division circuitry, originally developed for tuning fork regulated calibers, showed unsatisfactory performance concerning the energy consumption. After outsourcing the development of the integrated circuitry to the company Faselec in July 1966, one first prototype in form of a pendulette was build and assembled at Faselec in Zurich, which contains the first generation of integrated frequency division for portable quartz movements made. As mentioned above, the versions developed prior in the lab of Kurt Hübner were destined to run tuning fork regulated watches. To circumvent the lasting problem of battery life, the Beta project was split into two sub-projects in November 1966: Beta 1 and the alternative Beta 2 project (1).

Beta 1: The First Quartz Wristwatch

The Beta 1 project lead by Armin Frei would produce the very first working wrist watch sized quartz system. The first unit of a series of five was assembled and tested at the CEH in July 1967 by Jean Hermann and François Niklès. Since Seiko does not communicate any details about their first quartz wristwatch, one can firmly conclude that Beta 1 was the world’s first quartz wristwatch sized movement. For demonstration purposes, the new movement was packed into a standard square case (right picture), this was necessary because the quartz movement plate itself was rectangular with a length of 27 mm (1).

Beta 1 was equipped with a stepping motor activating the second hand step by step. The alternative and later model Beta 2 was equipped with the same quartz oscillator like Beta 1, but the second hand was actuated by a 256 Hz vibrating motor and a ratchet wheel with a smooth and continuous movement of the second hand (1).

Beta 1 – Components

Quartz Resonator:

While the size of commercial quartz standards in those days was as big as radio tubes, it was necessary for the quartz to be small enough to allow the device to be mounted inside wristwatch case. To keep the electronics simple, the frequency had to be 2 to the power of n (n being an integer) in Hertz in order to produce pulses with a period of one second at the end of the divider chain. Requirements which are very much contradictory, because if the dimensions are reduced the frequency increases and vice versa. Further, experiments have shown, that quartz resonators with the shape of a tuning fork (as used by Seiko) and fabricated with the technology of those days exhibit a much inferior factor of quality Q as compared to straight quartz bars. Armin Frei had manufactured tuning fork shaped quartzes by trying to glue three parts together, but glueing the quartz was not reliable enough and the experiments were abandoned (13).

The solution to all these requirements was a rectangular quartz bar with a length of 24 mm and with an frequency of 213 = 8192 Hz. The small dimensions of the quartz in its metal case as well as the extremely stringent requirements of mechanical precision, stability and lifetime required special attention with regards to most of the physical parameters: Leakage rates of the case and its feed-through had to be inferior to 5 10⁻¹² Torr ltr/s, organic and inorganic deposition on the surface had to be less than 20 Angstrom thick, metallurgy and soldering of wires onto the quartz surfaces had to be free from any unwanted inclusion, high precision soldering within a fraction of one millimeter was required to reach high quality factors of the resonator and many others. The quartz on the picture was developed and tested by Armin Frei in 1965, Oscilloquartz SA in Neuchâtel provided the raw material and Richard Challandes was responsible for the assembly. Rectangular cut bar quartz, similar to the one on the picture but with increased frequency, had been produced in Switzerland for watches until 1976, when first tuning fork shaped quartzes were imported from the USA and then ultimately produced by Ebauches SA (1).

Oscillator Circuit:

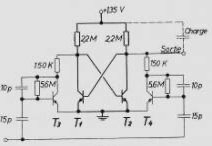

A number of different circuits for driving quartz oscillators were available at that time (Clapp oscillator, etc.), none of them fulfilled the necessary requirements for the quartz wristwatch, which would be: no coupling capacitances, low number of total resistors on the chip, tolerance to the integrated circuits fabrication process and its deviations, rigid operational stability and low power consumption. The newly developed symmetric cross coupled driver circuit as shown on the picture, incorporates a minimum of four resistors (Rc, Rₑ) , as well as two transistors (Tr₁, Tr₂) and fulfils the above requirements extremely well. The circuit was very tolerant to various applications and conditions, and easy to fabricate. It took the specialists of the semiconductor pilot line, Raymond Guye and his colleagues, less than two months to ship the first fully integrated properly working chips. The circuit was developed and tested by Armin Frei in 1965 and 1966 (1).

Frequency control:

The first step in the process of adjusting the frequency to the desired value was carefully grinding off surplus material and add weight at the ends of the quartz bar until a frequency was reached which, after evacuation of the case, resulted in exactly 213 Hz. A very difficult and tedious job indeed. A 14 stage divider chain would bring this frequency down to exactly 0.5Hz required to drive the stepping motor. To take care of the aging of the quartz and other disturbing later effects and during wear, a fine tuning mechanism was needed. A stepwise variable capacitor was hooked up in series with the quartz to change the oscillating frequency of the quartz assembly by 0.2 sec/day upward or downward (picture). At that time, Fritz Leuenberger of the semiconductor department started his research on MOS transistors, an excellent chance to integrate on a single chip a series of discrete MOS capacitors, high value and small volume, exactly what was wanted. The design and layout was made in 1966 by Armin Frei, the semiconductor department delivered the MOS capacitor chip and the watch maker technician Claude Challandes designed the miniature switch (1, 13).

Frequency Divider:

Since the very beginning of the quartz wristwatch project, Armin Frei decided that the oscillating frequency of the quartz had to be 213 = 8192 Hz. Consequently, for Beta 1 using a stepping motor to drive the second hand, see below, a total of 14 binary flip-flop stages were required to drive the motor of the watch with pulses of 0.5Hz. Rolf Lochinger was appointed head of the frequency divider development, after terminating the ill fated atomic decay project. The flip-flops which were finally incorporated in the Beta 1 prototypes, were designed by Jean Fellrath, constructed by Jean-Daniel Chauvy and implemented in integrated form by Raymond Guye and his group in bipolar technology. The circuits were optimised for low power consumption of approximately one microamp per stage and for high operational stability. In bipolar technology the divider chain with 14 stages represented a big load for the battery, limiting its lifetime to less than one year, much to the concern of certain members of the governing board. The immediate solution to that would have been a reduction of the number of divider stages, say 5, reduce the frequency to 256 Hz rather than 0.5Hz and use a vibrating motor rather than a stepping motor. This was alternatively proposed with the Beta 2 and later the Beta 21 projects in August 1967 and late 1968 respectively. However, the real solution to the power consumption problem would ultimately have been the use of the Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor circuits (CMOS), which had been invented in USA (Frank Wanlass, 1963) a couple of years before, and were researched by the CEH, but were regarded as not reliable enough for the use in wrist watches (1, 15).

Temperature Compensation:

The irregularities in timekeeping of quartz wristwatches are due to the temperature sensitivity of the various physical parameters of the quartz crystal itself and are not due to the electronics attached to it. The deviation in time is measured in seconds per day as a function of temperature. The resulting plot, usually displayed between 4° C and 36° C is a complicated function of the cutting angles relative to the axes of the quartz crystal itself. At the time, it was well known that the rectangular quartz crystals exhibit parabolic curves according to the curve a) in the picture. The engineers were very much aware that the manufacturers of the current mechanical watches were keen to keep the temperature deviation as small as possible, so engineers engaged strongly in the disciplines of temperature compensation. First investigations using temperature sensitive resistors and capacitors were not very successful. Jean Hermann proposed in 1967, shortly before the very first quartz wristwatch was operating, a scheme using the parabolic behaviour twice and a switch to connect a compensating capacitor at 12° C according to curve b). This scheme was easy to implement, produced favorable results with the observatory tests and would be effective during daily use. Yet, it required extensive interventions by the laboratory director on behalf of the department head in order not to drop the brilliant idea. The resulting Thermo Compensation Module (TCM) was developed by Jean Hermann and was implemented using MOS technology by Fritz Leuenberger and his group in 1967. This temperature compensation module was one of the main reasons why the CEH watches performed better than the watches by Seiko during the observatory competition, see below (1, 16).

Stepping Motor:

All that was left was to convert the pulses appearing at the end of the divider chain into step by step advancements of the second hand. Jean Hermann and François Niklès proposed in 1967 a simple solution of such a stepping motor for Beta 1, as seen in the picture. The setup incorporated an anchor wheel and an anchor which were responsible for the movement of the second hand. Much different as in mechanical watches, where the anchor and the anchor wheel act as escapement, here the anchor drives the anchor wheel by wiggling back and forth. The anchor was activated by means of a bobbin coil, which was attached to the anchor and which was magnetised by bipolar electric pulses. The duration and the amplitude of the pulses had to be well controlled to warrant proper operation and to save battery power. The duration of the pulses was derived from the pulse pattern appearing along the divider chain using boolean logic. The concept and the basics had been worked out as early as 1966 (1).

Beta 2

As mentioned above, prior to November 1966, the governing board of the CEH had little sympathy for the new direction concerning the Beta quartz wristwatch project. They were hoping for an electronic, tuning fork regulated watch, double the precision of the ‘Accutron’, exhibiting at least one advantage compared with existing electronic watches and here was a watch (Beta 1) with a battery lifetime of about 4 months! One representative of the governing board made it a must: ‘Battery lifetime had to be equal or longer than one year’. A thick battery was chosen, type WH3 from Mallory, with a capacity of 165 mAH at 1.35 V. The Beta 2 concept was adopted, as the only one able to keep the over-all current consumption below 18 µA (1, 3, 16).

Max Forrer was closely working together with Henry Oguey on the Beta – tuning fork project, where Oguey had made impressive progresses with developing a vibrating motor. This motor was vibrating at 256Hz, so it was clear that the frequency division from 8192Hz of the quartz to the 256Hz of Oguey’s vibrating motor would take less components and thus less energy. Following this hypothesis Max Forrer and Henry Oguey proposed and initiated in November 1966 an alternative Beta – quartz project called Beta 2. For this alternative project the principles of Beta 1 were kept, so the quartz oscillator with his circuitry was identical to Beta 1, the principle of binary frequency dividers and the motor had to be adapted (1, 3).

With a motor vibrating at 256Hz it would need only 5 binary flip flops for frequency division and as the motor was at the final steps of development already, it was possible to construct a working prototype by August 1967, one month later than Beta 1. Because of the reduction of the elements needed for frequency division (5 instead of 14 in Beta 1) the energy consumption could be optimised for the battery to last over one year, fulfilling one of the main criteria of the governing board (1, 3).

1967: Trials at the Neuchâtel Observatory

Beginning in January 1967, two teams had started the final drawings for two complete quartz watch prototypes. The volume and thickness of the movements had to comply with strict conditions in order to be accepted later by the Neuchâtel Observatory contest, in the wrist watch category. Both solutions generated an exciting competition between the two developing teams. About one month after its manufacture, in August 1967, the first quartz wristwatch Beta 1 with connotation CEH-102 was delivered to the Observatory of Neuchâtel and was immediately submitted for tests in the new category of ‘electronic wrist watches’. The resulting number of classification was 0.189, a value at least one order of magnitude better than the other mechanical competitors in the same category. The first Beta 2 were submitted for tests at the observatory in September 1967. All along the last months of 1967, 11 of the 20 hand made Beta 1 prototypes (numbered CEH-1xx, why these have been renumbered CEH-1xx0 on paper during the observatory competition remains unknown) and Beta 2 prototypes (numbered CEH-2xx) were brought to the Neuchâtel Observatory personally by Jean Hermann for precision testing (1, 16).

The 11.11.1967, also 4 pieces from Seiko (numbered W-0xx) entered the competition. The remaining CEH prototypes did not make the top 15 at the competition or did not enter the competition. Also absent was a fifth movement from Seiko, which unfortunately didn’t survive shipping from Japan (5, 7).

The results can be seen below: The first 10 places and place 12 were taken by the CEH prototypes. The different classification was due to variation of temperature compensation and regulation and not due to construction variability (1).

After the celebration of the outstanding results reached with Beta 1 and Beta 2 following the observatory tests in 1967, finally published the 15.02.1968, investigations on how to establish a technology transfer from the prototypes towards an industrial product started immediately. First, it was decided to favour Beta 2, not Beta 1. This decision was commented by Henry Oguey and Henri Schneider simply by (1):

“Au vu de l’expérience acquise sur les prototypes, seul le système Bêta 2 entre en ligne de compte pour assurer une durée de vie de la pile supérieure à un an.”

(In view of the experience acquired with the prototypes, only the Beta 2 system can be considered to ensure a battery life of more than one year).

*** Continues in subsection ‘Beta 21‘ ***

Ref.:

- Quartzwristwatch, Courtesy of Dr. Armin H. Frei Heritage Estate

- Grail Watch

- Watch Wiki

- ETA

- Personal communication with former engineers at CEH, working on the development of the Beta 1, Beta 2 and Beta 21 prototypes, as well as Beta 21 industrial production

- Laptrinhx

- Eperiodica

- Forrer M., LeCoultre R., Beyner A., Oguey H.; L’aventure de la montre à quartz, Centredoc, 2002

- Observatoire Cantonal de Neuchâtel, Rapport annuel du Directeur sur l’exercice, 1967

- Trueb L. F., Ramm G., Wenzig P.; Die Elektrifizierung der Armbanduhr; Ebner Verlag, 2011

- Crazywatches

- Piguet Ch.; Integrated Circuit Design Power and Timing Modeling, Optimization and Simulation 12th International Workshop, PATMOS 2002 Seville, Spain, September 11-13, 2002, B. Hochet, A. J. Acosta, M. J. Bellido (Eds.), Springer

- Personal communication with a former Executive Vice-President of Ebauches SA, in charge of Research & Engineering

- Vittoz E. A.; The Electronic Watch and Low-Power circuits; IEEE Solid-State Circuits Newsletter, February 2008

- Roger Wellinger Archive

- Privately written notes by Armin Frei and Rolf Lochinger

- Chronometer bulletins of the respective Beta 1 and Beta 2 prototypes