19min read

The base for the later Seiko is founded in 1881 by Kintarō Hattori in Tokyo, at first as a watch and clock retail and repair store, earning the trust of foreign trading companies, the business expands greatly. Building on the success of the retail business, 1892 ‘Seikosha’ (meaning ‘House of Exquisite Workmanship) is founded and commences with manufacturing wall clocks. While Seikosha continued to produce clocks, Daini-Seikosha was established in 1937 as a second company with a focus on watch production. In 1944, due to the war, a factory was established in Suwa as a part of Daini-Seikosha. After WWII this location continued operation and in 1959 it was separated from Daini-Seikosha to create the new company Suwa-Seikosha (2, 4, 9, 20, 23).

Precision Timekeeping

Seiko was always concerned about offering the best quality and most precise time keepers and had been participating in precision horology competitions throughout the 1950s that were conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Commerce and Industry, established to compare the domestic watch production quality to that of international brands. These Japanese domestic competitions concluded in 1960 (23).

In 1959, the Neuchâtel Observatory competitions were opened up to non-European entrants. In 1962 Seiko contacted the Observatory and was advised that the Observatory would welcome the participation from Japan. They provided the competition regulations and relevant materials to Seiko (2).

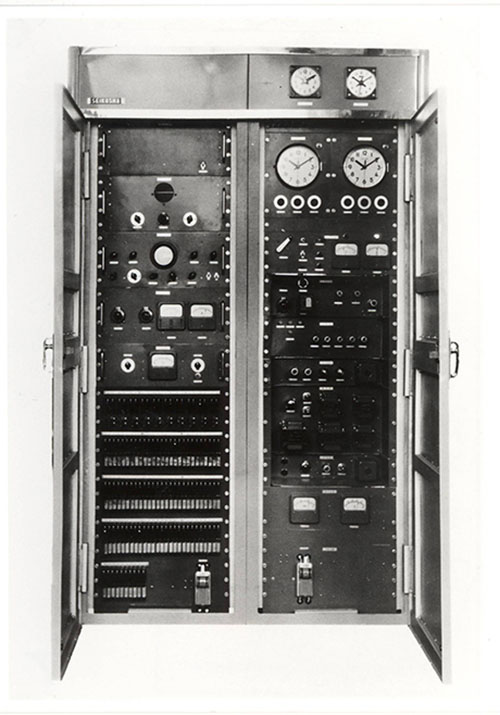

Additionally, when it was decided, during the 55th IOC Session in then West Germany on 26.5.1959, that the summer Olympic Games in 1964 would be held in Tokyo, Seiko’s ambition was to provide the precision timing for it and continued its research into quartz regulated time pieces, which had started with the building of a big quartz clock in 1958 for broadcasting stations (5, 11).

Suwa – Seikosha

In 1959 Suwa decided to entrust engineer Tsuneya Nakamura with project ‘Gojukyu-A’ for which he would need to scientifically analyse alternative physical, horological processes for wrist watches. Nakamura was specialist in quality optimisation and he had proven his talent with the development of the mechanical ‘Marvel’ model in 1956. He started the new project with a team of 7, which will grow to 30 a few years later (12, 15).

When analysing the ‘Accutron’-system launched in October 1960, Nakamura’s team realised quite quickly the major functional flaw of the system: position errors. Moreover, Nakamura was not convinced about the reliability of the index system of Accutron’s ‘motor’, which he judged too fragile. The only promising and potentially reliable system, which Nakamura would want to pursue, would be the quartz system (12).

Nakamura had to overcome fierce opposition by some Suwa management members, but his arguments about highest possible precision of the quartz system would convince them. Moreover, it was known, that sister company Daini-Seikosha and especially the Swiss were working on the quartz system too. After merging expertise with Daini and participating to the development of the ‘Crystal Chronometer’ for the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, Nakamura’s team worked uninterruptedly for the further miniaturisation of the quartz system. The increasingly good results of their quartz entries for the 1965 and 1966 Chronometer competitions in Neuchâtel confirmed the direction taken by Nakamura’s quartz laboratory. Nakamura’s team members lived in close proximity of the facility and the laboratories were open for 24h, so the engineers could and would return back to work even after dinner. The hard work paid off, as in November 1967, Seiko entered several wrist watch sized quartz prototypes to the Chronometer Competition in Neuchâtel and thus participated to the ‘quartz revolution’ starting that year (12, 18).

Nakamura’s interest did not lie solely in chronometer competitions, his ambition from the start of the developments was to develop the most precise, reliable and robust, industrially produced quartz wrist watches. Thus, a team of 5 engineers within the quartz laboratory was made responsible for production relevant aspects of the new technology, which were constantly integrated into the development. This production strategy was adopted from the American way of automatising and optimising watch caliber production since the late 19th century. Already the development and production of the American ‘Accutron’ benefitted from this method. This integrative strategy would ensure a certain advantage compared to the Swiss, who would need complex, intermediary phases of technology transfer from their chronometer competition prototypes to engage in industrially compatible production. (12, 16, 17, 19).

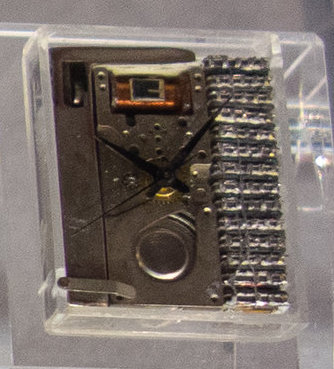

Therefore, starting 1968 the system used in the chronometer competition prototypes was quickly adapted for production and the resulting caliber for the model ‘Astron 35SQ’, which retained the prototypes principles of hybrid integrated circuitry with 76 transistors, 29 capacitors and 84 resistors on a ceramic platelet, a tuning fork shaped quartz and a stepping motor. The latter two features would become the gold standard for quartz watches to this day (12, 15).

The exact production numbers of the Seiko Astron 35SQ are shrouded in mystery, whereas some sources state that the total production was of about 200 pieces, a realistic review of the market and the regularity that these models turn up for sale would indicate that the total number is more than 200. The first 100 watches made in 1969 were marketed in December of the same year, making the Seiko ‘Astron’ the worlds first commercially available quartz wrist watch (12, 15, 23, 26).

Daini – Seikosha

The Seikosha facilities in Daini were destroyed during WWII and for the reconstruction of the firm the engineer Kouji Kubota was entrusted with the development of an automated way to assemble mechanical movements with interchangeable pieces starting from 1947. With the launch of the ‘Accutron’ in 1960, Kubota’s team faced suddenly a new horological system with a factor 10 of precision increase, as compared to the mechanical calibers they were specialised in (13).

When reconstructing the principles of the ‘Accutron’ in their own lab, Kubota’s team quickly realised the flaws of the system, as also the engineering team at Suwa did. Consequently, Daini and Suwa worked on their own tuning fork system obtaining a Japanese patent the 18.2.1961 for a transistorised tuning fork caliber using a titanate-barium tuning fork. The material used for the tuning fork revealed to be unreliable with the available batteries, and the project was abandoned (13, 14).

Despite its technical flaws, Daini strived to obtain a licence from Bulova. However, Bulova wanted to keep the monopoly of the ‘Accutron’ system as long as possible and as by 1963 the negotiations with Bulova failed, it was decided to pursue the even more promising quartz path. The negotiations for a licence failed, also because Bulova was in negotiations with Citizen, later including the use of the Accutron 218 movement (introduced 1967) and with Ebauches SA for the industrialisation of their MOSABA caliber. Citizen finally would receive a worldwide exclusive licence by Bulova to use their Accutron 218 movement and Ebauches SA would obtain a licence at huge costs, to be able to market their MOSABA tuning fork movement starting in 1968 (1, 21).

Daini had good relationships with Tokyo University and had a consulting contract with Professor Takami. Takami was highly interested in the quartz system for time pieces and he calculated on theoretical basis, the potential precision of quartz calibers of different sizes. The results of Takami’s reserach were the basis for the decision to develop the ‘Crystal Chronometer’ for the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo in collaboration with Tsuneya Nakamura’s team at Suwa. However, the most important personality for its development was Daini’s engineer Masatoshi Tohyama, who had even the honour to explain the functioning of the ‘Crystal Chronometer’ to the then crown prince and later Emperor of Japan, Akihito (1, 9, 13).

Observatory Competitions in Neuchâtel

The earliest competition quartz developments culminated in 1963, where Suwa-Seiko became the first Japanese company, to join the Neuchâtel Observatory chronometer competitions. The company entered their new ‘Crystal Chronometer’ of Marine Chronometer size. All entries in the Marine Chronometer category from Suwa-Seiko in 1963 were regulated by Tsuneya Nakamura himself. The scores for Suwa-Seiko were a good first attempt from the company, but not at the same level as the other entrants (2, 12, 15).

Suwa returned to the Neuchâtel Observatory competitions in 1964 with quartz entries in the Deck Chronometer category, this time regulated by Susumu Aizawa. Daini would enter mechanical watches to the competitions, but they did not enter a quartz product in any category, despite entering the production of quartz watches later on, see below. The precision results of Suwa’s quartz entries were much better in 1964, ranking second after Longines. In 1965 the great performance was repeated, again staying close behind Longines. In 1966, apart of entries in the Deck chronometer category, Suwa also provided entires in the pocket chronometer category, where again Longines took the first place, with their L400 quartz pendulette (2, 15).

The Wrist Watch sized Quartz Revolution of 1967

The Japanese wrist watch sized entries for the Chronometer Competition at the Observatory in Neuchâtel 1967 arrived in November by mail directly at the Observatory. The testing for the first Seiko quartz caliber was scheduled for the 11.11.1967. The Swiss wrist watch sized developments Beta 1 and Beta 2 by the CEH are thoroughly discussed in the respective sections. It is interesting to compare the wrist watch sized quartz movements developed by the CEH in Neuchâtel with the ones made by Seiko (1, 18).

Both, the Swiss and the Japanese, used a quartz resonator with a frequency of 8’192 Hz as their oscillator. In Japan, however, it was shaped like a tuning fork (the future standard), while in Switzerland the custom was to use simple, bar shaped quartzes. In both cases, division by multiples of two provided the low-frequency signal required to drive a motor: Stepping motor for Beta 1 and the Seiko prototypes, vibrating motor for Beta 2. But frequency division took very different paths. While the CEH used bipolar integrated circuits, at Suwa the circuit consisted of a hybrid system. Nakamura, realised already in 1961, that index fingers as used in the motors of the American Accutron, and later the Swiss Beta 2, Beta 21 and the Longines’ ‘Ultra-Quartz‘ would represent structural weaknesses, therefore his team would concentrate their efforts on creating a stepping motor with the corresponding frequency division circuitry. This strategy would reveal to be wise, as stepping motors would become standard for quartz watches later on. Therefore, if analysing the earliest Seiko quartz wrist watch prototypes of 1967 in detail it can be seen, that they incorporate already many features, which would become international standard for wrist watch sized quartz calibers and also the Swiss will abandon the early bar shaped quartzes and consistently turn to the combination of tuning fork shaped quartzes and stepping motors by 1976 (1, 6, 12).

The Global Leadership U-Turn

Before the acceleration in refinement of the ‘ion implanting process’ towards 1965 in the USA, it was not possible to industrially mass produce reliable, integrated circuits. This new method, more reliable starting 1967, greatly contributed to the revolution in microelectronic research and application. The American microelectronics industry took advantage of this new method to develop and industrially produce low power CMOS circuits, at first used in the military and space research. The ion implantation technology was invented by ‘Hughes Microelectronics’ in Newport Beach. This company, funded by the US Department of Defence, had the mission to develop radiation resistant microelectronics to be used in nuclear missiles. The enormous investments paid off, when the mentioned ‘ion implanting process’ was invented. This new system for making low power CMOS integrated circuits was later licensed to other American microelectronic companies (1, 11)

The Swiss engineer Jean Hoerni, at the forefront of these developments at ‘Fairchild’, had decided to leave the company and create ‘Intersil’ (INTEgRated SILicon) in 1967, wanting to specialise in just these low power CMOS integrated circuits, specifically for use in wrist watches. Huge investments were necessary and at first without the possibility of ion implanting, most probably using deep diffusion and phosphorous gettering by January 1969 he and engineer Luc Bauer had adapted the ‘Intersil’ CMOS system to run and control 16KHz quartzes and which provided a frequency division to 1Hz. The reliability was quite bad, only a few of several hundred produced IC’s were working properly, but Hoerni had working prototypes and the technology was almost ready to be fitted inside wrist watch sized calibers (1, 11).

Swiss watchmaking companies (Omega, Portescap and Universal Geneve) invested in Hoerni’s ‘Intersil’ and Omega directly took advantage of a scientific collaboration with Jean Hoerni for the development of in-house (at Battelle) MOS IC’s to be integrated in their high frequency quartz development of prototype cal.: 1500, which will later become cal.: 1510 for the model ‘Megaquartz 2.4MHz’ (1, 7).

However, by march 1969, Hoerni needed more important investments, to finally invest into a licence from ‘Hughes Microelectronics’ for using the ion implanting technology and the highly complex machinery, which was extremely expensive (ca. 5 Mio $ per machine). His first step was to present his CMOS IC prototypes to the Swiss shareholders of ‘Intersil’ and ask them for more investments to complete his development, but unfortunately they were not interested (1):

Omega was developing and financing the costly 2.4MHz high frequency movement with Battelle (and Hoerni as consultant) and in parallel contributing to the CEH developing the end stages of the Beta 21. Omega’s Hans Widmer did not want to diversify into one further frequency (16KHz), which would have needed yet another adaptation and a new caliber development (1).

Portescap’s George Braunschweig recognised the importance of Hoerni’s low power CMOS, but as the most lucrative product of Portescap was the ‘Incabloc’ system for mechanical watches, it would have been silly to further invest into a technology which would risk to undermine the ‘Incabloc’ distribution. Later Portescap will diversify their expertise by providing mechanical motor elements for quartz timekeepers (1).

Universal Geneve, committing to the tuning fork system as innovation (being a subsidiary of Bulova since 1967) and thus officially not really interested yet in the use of the quartz system, also did not invest further into Hoerni’s CMOS venture. Universal Geneve will present the ‘Uniquartz’ at the Basle Fair 1970, with cal.: Beta 21, despite officially not having been part of the CEH (1).

The biggest shareholder of ‘Intersil’ was the Italian Olivetti, which was transitioning from producing mechanical writing machines to electric writing machines, but would not be in immediate need of CMOS technology to do so (1).

In desperate need of money and after two hopeless weeks in Bienne, Hoerni turned to collaborators at General Electric for advise. The most promising hint was to ask Toshiba in Japan, which licensed many products from General Electric to be used domestically. The contact at Toshiba forwarded Hoerni the direct phone number of Reijiro Hattori, chairman of the Seiko Corporation. After a first contact by phone, Hoerni was invited to Japan to meet Hattori, who, upon the presentation of Hoerni’s first low power CMOS IC prototypes, made Seiko immediately sign a technology and license agreement with ‘Intersil’ for investments. This important investment by Seiko enabled them to exclusively receive first big batches of the first industrially produced, low power CMOS IC’s to be integrated into their quartz wrist watch developments by the beginning of 1970. The electronics research in Japan was extremely advanced and after a short period of transition, Seiko managed to use in-house IC’s for their further quartz watch developments, see below (1, 22).

Paradigm Shift

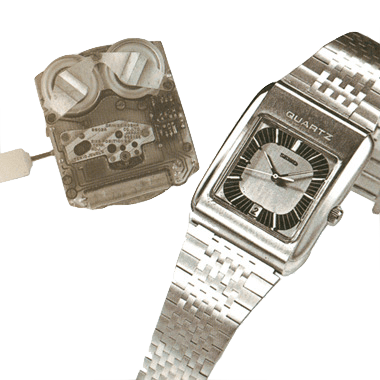

The first commercial wrist watch quartz model from Seiko, the Astron 35SQ, produced from mid 1969 to 1970 had hybrid electronic elements assembled by hand, but already the next Seiko (Daini) quartz model, the 36SQC (cal.: 3922A), produced at the end of 1970 was equipped with these industrial, low power Intersil CMOS circuits and fitting 16KHz tuning fork shaped quartz resonators and is thus the worlds first CMOS equipped quartz wirst watch. It seems remarkable that Seiko managed to adapt that fast to the new technology and develop a quartz wrist watch with industrial grade CMOS technology as early as 1970/71. Continuing with the successful, integrative development strategy and having already set the standards using tuning fork shaped quartzes and the consistent use of a stepping motor since 1967, it was relatively straight forward to adapt the existing system to a more powerful electronic element with corresponding 16KHz quartz and thus remain several steps ahead of the Swiss developments (1, 9, 13, 25).

However, conversations Anthony Kable had with Seiko staff, when discussing the rarity of this 36SQC model revealed, that essentially all of the 36SQC’s produced were returned due to operational issues. It seams that the only surviving example of a 36SQC is exhibited at the Seiko museum in Ginza. Examples of this watch just do not turn up at auction or for sale in Japan, and are orders of magnitude rarer than the Astron (23).

In line with the above, engineer Kouji Kubota was not satisfied with the Intersil IC’s and as reaction a subsidiary of ‘Intersil’ named ‘Micro Power Systems Inc.’ in Santa Clara, California was founded in 1971. Seiko was shareholder of the new company and would produce CMOS IC’s under ‘Intersil’s license there. The technology transfer from the new company in California to Seiko in Japan happened quite fast and was enabled by the installation of an in-house semiconductor laboratory for researching and fabricating CMOS IC’s, also under Intersil’s licence. Therefore, Seiko had two facilities, one in California and one in Japan, which in parallel would produce and research CMOS IC’s. These parallel facilities, one of which in closest proximity of ‘Intersil’, explains the very fast technological advancements Seiko could perform. Seiko’s future quartz developments would thus incorporate in-house CMOS IC’s, but this was not enough for Kubota’s engineers, they would soon find a way to incorporate more functions, such as alarm and chronograph to the electronic technology (1, 13, 16, 22, 23).

Following this first injection with low consumption CMOS integrated circuits from ‘Intersil’ and the following integration and improvement of this technology for creating in-house IC’s, Seiko could start its ascension of producing a big amount of high quality, very precise and affordable quartz watches. An ascension, which by 1977 will highly contribute to project the Swiss watch industry into its most important crisis (1, 13).

Industrial Espionage

It is interesting to note, that the early electric and electronic developments of the Japanese and the Swiss watch manufactures took similar intermediary steps and show very similar developments almost simultaneously. Also some details of the technological solutions for creating the first wrist watch sized quartz calibers are very similar. Despite the confirmation, that the Swiss analysed the Japanese developments very closely and vice versa, representatives of both parties confirm convincingly, not to have known about the developments of the other prior to their publication (1, 12, 13).

It can be strongly assumed, that all early quartz developments were created independently from each other and it is thus interesting, that the technological advances in electronics were exploited in very similar ways, in parallel and in opposite parts of the world. Despite the mentioned technological variations with better long term solutions by Seiko (tuning fork shaped quartzes, stepping motor), the main difference between the Swiss and the Japanese was not on the level of the engineering, but lies in the different strategies for the industrialisation of their respective developments, which clearly advantaged the Japanese industry (1, 16).

Acknowledgements: This article was made possible thanks to the generous contribution of Anthony Kable (@plus9time, plus9time.com), a renowned expert in Seiko’s developments.

For further information about the developments at Seiko, please visit following sites: Plus9time, The Grand Seiko Guy, The Seiko Guy

Ref.:

- Personal communication with a former Executive Vice-President of Ebauches SA, in charge of Research & Engineering. He was a good friend of Jean Hoerni, Reijiro and Ichiro Hattori and received the info directly from them.

- Plus 9 Time

- Worn and Wound

- Wikipedia – Seiko

- Wikipedia – 1964 Summer Olympics

- Trueb L., Les premières montres-bracelets Quartz en Suisse et au Japon; Histoire de la montre à quartz, Bulletin SSC n° 63, Mai 2010

- Ryssel H., Chapter 1: Ion Implantation into Semiconductors: Historical Perspectives; Gerard Ghibaudo, Constantinos Christofides; Semiconductors and Semimetals, Elsevier, Volume 45, 1997, Pages 1-29,

- Chiphistory

- Seiko

- Jacques Maillot, Camera Press, L’Express, London

- Seiko Museum

- Transcription of a recorded interview of Lucien Trueb with Tsuneya Nakamura, published in: Trueb L., Zeitzeugen der Quarzrevolution, Editions Institut l’homme et le Temps, La Chaux-de-Fonds, 2006

- Transcription of a recorded interview of Lucien Trueb with Kouji Kubota, published in: Trueb L., Zeitzeugen der Quarzrevolution, Editions Institut l’homme et le Temps, La Chaux-de-Fonds, 2006

- Hetzel M., La Montre Electrique; Conference de Synthese, Societé Suisse de Chronométrie, June 1964

- Fratellowatches

- Donzé P.Y., Dynamics of Innovation in the Electronic Watch Industry: A Comparative Business History of Longines (Switzerland) and Seiko (Japan), 1960-1980, The Journal of the Economic & Business History Society , © 2019, The Economic and Business History Society.

- Watchonista

- Observatoire Cantonal de Neuchâtel, Rapport sur le concurs chronométrique, 1967

- Donzé P.Y., The Hybrid Production System and the Birth of the Japanese Specialized Industry: Watch Production at Hattori & Co. (1900-1960), Enterprise & Society, Volume 12, 2011

- Seiko Design

- My retro Watches

- Trueb L. F., Ramm G., Wenzig P.; Die Elektrifizierung der Armbanduhr; Ebner Verlag, 2011

- Personal communication with Anthony Kable (plus9time.com; @plus9time)

- Olympics.com

- Seiko Instruments Inc.

- The Seiko Guy